A new study shows that the protein CHIP can regulate the insulin receptor more efficiently alone than in a paired state. In cellular stress situations, CHIP usually appears as a homodimer - an association of two identical proteins - and primarily serves to degrade misfolded and defective proteins. CHIP thus cleans up the cell. To this end, CHIP collaborates with helper proteins to attach a chain of the small protein ubiquitin to misfolded proteins. The defective proteins are thus recognized and eliminated by the cell. In addition, CHIP also regulates the signal transduction of the insulin receptor. CHIP binds ubiquitin to the receptor to degrade it and stop the activation of life-extending gene products.

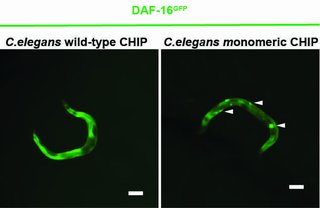

A Cologne-based research team led by Prof Dr Thorsten Hoppe has now shown in experiments with the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and human cells that CHIP can also label itself with ubiquitin, which prevents its dimer formation. The CHIP monomer is more efficient than the CHIP dimer in regulating insulin signalling. The study by the University of Cologne’s Cluster of Excellence for Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases (CECAD) was published in Molecular Cell under the title ‘A Dimer-Monomer Switch Controls CHIP-Dependent Substrate Ubiquitylation and Processing’.

“Whether CHIP works alone or as a pair depends on the state of the cell. Under stress, there are too many misfolded proteins as well as the helper proteins that bind to CHIP and prevent auto-ubiquitylation, the self-labelling with ubiquitin,’ said Vishnu Balaji, first author of the study. ‘After CHIP successfully cleans up the defective proteins, it can also mark the helper proteins for degradation. This allows CHIP to ubiquitylate itself and function as a monomer again,’ he explained. Thus, for the body to function smoothly, there must be a balance between the monomeric and dimeric states of CHIP. “It’s interesting that the monomer-dimer balance of CHIP seems to be disrupted in neurodegenerative diseases,’ said Thorsten Hoppe. ‘In spinocerebellar ataxias, for example, different sites of CHIP are mutated, and it functions predominantly as a dimer. Here, a shift to more monomers would be a possible therapeutic approach.’ In the next step, the scientists want to find out whether there are other proteins or receptors to which the CHIP monomer binds, and thus regulates their function. The researchers are also interested in finding out in which tissues and organs and in which diseases CHIP monomers or dimers occur in greater numbers, in order to be able to develop more targeted therapies in the future.

Media Contact:

Professor Dr. Thorsten Hoppe

+49 221 478 84218

thorsten.hoppeuni-koeln.de

Press and Communications Team:

Dr. Anna Euteneuer

+49 221 470 1700

a.euteneuerverw.uni-koeln.de

Publication:

Balaji V, Müller L, Lorenz R, Kevei E, Zhang WH, Santiago U, Gebauer J, Llamas E, Vilchez D, Camacho CJ, Pokrzywa W, Hoppe T. A Dimer-Monomer Switch Controls CHIP-Dependent Substrate Ubiquitylation and Processing. Mol Cell. 2022

https://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/fulltext/S1097-2765(22)00756-0