Archaeological research on the Palaeolithic Age reveals that the presence and actions of humans can increase the biodiversity of an ecosystem – under certain conditions.

Today’s biodiversity loss fundamentally threatens the habitability of the Earth and is therefore one of the most important challenges of our time. The roots of this problem go way back in time. After the modern human Homo sapiens left the African continent around 100,000 years ago, major extinction events ensued around the globe. In particular, the so-called megafauna – such as the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, diprotodon and Irish elk – slowly but surely disappeared wherever humans appeared. Large predators such as the cave lion and giant short-faced hyena also became extinct at the end of the last ice age.

The extent to which only humans or climate change from cold to warm periods triggered the mass extinction at the end of the Pleistocene up to 10,000 years ago is often debated by the scientific community. However, the biodiversity loss in the Anthropocene, i.e. the reduction of species under the influence of humans, is widely accepted. The question is: Is this really always the case? And how destructive is humankind for the environment?

Looking back on the early days

Archaeologist Dr Shumon T. Hussain from the Cologne research hub MESH (Multidisciplinary Environmental Studies in the Humanities) focuses on this question in his research. The research centre addresses the social, cultural and ethical dimensions of global environmental change and the associated ecological, climatic and health crises.

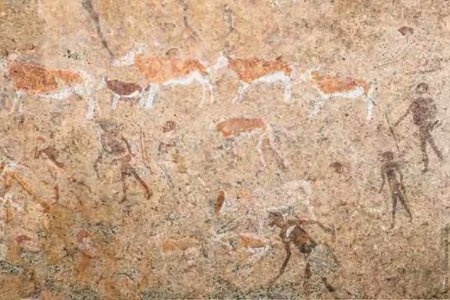

Using case studies, the archaeologist and his colleague Dr Chris Baumann from the University of Tübingen are investigating the interaction of humans with various other species. There are two contradictory opinions: Since our evolution 300,000 years ago in Africa, Homo sapiens has inevitably wiped out other species, or at least threatened their existence. This ›killer hypothesis‹ is contrasted with the image of the ›good‹ humans of nature who lived in perfect harmony with their environment, even in the Palaeolithic Age. According to Hussain, the reality is much more complex. »The idea that humans lived harmoniously with nature as hunter-gatherers mischaracterizes the fundamental problem of human interaction with ecosystems,« explained the scientist, who has been studying the effects of the interaction of humans with other species in the Stone Age for years. »It is equally misleading to focus exclusively on the extinction events that occurred in the recent past, the so-called biodiversity loss in the Anthropocene, and to attempt to prove that people actively intervened in their ecosystem more than 10,000 years ago, notably with negative consequences.«

Raven, mouse and fox benefit from human influence

The relationship between humans and ecosystems has always been much more complicated and complex: In addition to negative effects, scientists also regularly record positive effects of humans on the biodiversity in ecosystems. »Oftentimes, it can even be said that biodiversity loss occurs locally due to human activity, but biodiversity is strongly promoted elsewhere; these dynamics must therefore be placed in a wider context,« said Hussain. These feedback systems between humans and the environment – with significant effects on biodiversity – are likely to be a recurring feature of the Late Pleistocene (the last phase of the ice age, which ended almost 11,000 years ago).

A current study by Hussain and Baumann on ravens from the ice age shows that these birds already benefited from humans as neighbours about 30,000 years ago – especially from food options that hunter-gatherers in the environment provided for these animals. Other opportunistic scavengers that benefited from human hunting include foxes, wolves and wild boars. But mice, sparrows and rats have also profited from the presence of humans in different contexts. The archaeologists based their investigations on the results of archaeozoological and so-called stable isotope studies, which were applied in the case of ravens. They used this and other previously published archaeological context information to show that such processes can lead to an increase in biodiversity on a local level. This is because certain animals benefit from human influence and others that are excluded locally by humans, such as larger predators, move to other areas. Overall, this increases the heterogeneity and complexity of such ecosystems, thereby often resulting in a positive effect on overall biodiversity in places inhabited by humans.

Homogenization instead of diversity

The results also point to the importance of the specific culture and economy of human societies as a shaping element for ecosystems and their composition. People function as ›guardians‹ of the ecological niche that they cultivate. According to the scientist, diverse forms of utilization of the environment and human lifestyles can thus promote a diverse and stable ecosystem. »Ultimately, we try to argue that biodiversity regimes cannot be separated from human influence and that not all of these influences are purely negative,« explained Shumon Hussain. The investigations into the Palaeolithic period also shed light on current problems: »It follows that increased diversity in human life forms probably has an overall positive effect on biodiversity as a whole, and that a decisive driver of the biodiversity crisis in the Anthropocene is the homogenization of human life in nature and with it.«

The archaeologists therefore recommend paying more attention to the complex relationships between biological and cultural diversity and taking a closer look at the role of humans as guardians of their ecological niche in order to understand it better in the long term. Hussain: »The promotion of biodiversity probably also depends on the promotion of cultural diversity.«